|

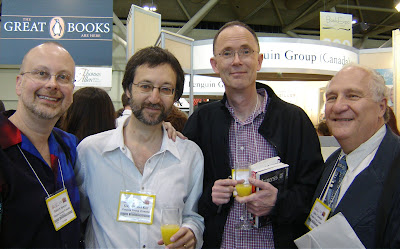

| Robert J. Sawyer, Guy Gavriel Kay, William Gibson, and John Robert Colombo (From: The Robert J. Sawyer Web Site) |

"Twenty years ago, when my third science-fiction novel came out, Books in Canada magazine profiled me. The profile’s author, quoted me as saying, 'Maybe it’s a grass-is-always-greener thing. But I can’t help thinking that writers working in almost any other area are getting more respect. It’s really very frustrating.' To which Weiner added: 'No respect. At times Sawyer seems about to slip into a routine. I can’t get no respect.'

Well, of course, in the two decades since, I’ve gotten a lot of respect. Just last month I received the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal from the Governor General’s office. And on March 18, McMaster University picked up 52 boxes of my papers to add to their Canadian-literature archives — surely a sign that SF is now part of the mainstream. […]

But in 2007, after I arrived in the Klondike at the famed writer’s retreat, I discovered the had, for the first and only time, overruled the unanimous choice of the selection committee in Dawson City, denying funding for my stay.

Nonetheless, I did what one is supposed to do: I wrote a novel inspired by my time in the Yukon. Red Planet Blues, set in the Mars colony of New Klondike against the backdrop of the Great Martian Fossil Rush, has just been published under Penguin Canada’s mainstream Viking imprint, debuting at No. 7 on the Maclean’s bestsellers’ list. It, too, had its grant application denied by the Canada Council — as did the new book I’m starting to write now."

— Robert J, Sawyer, Ottawa Citizen

Read more…

Pay your respects by purchasing one or all of Robert J. Sawyer's books here...